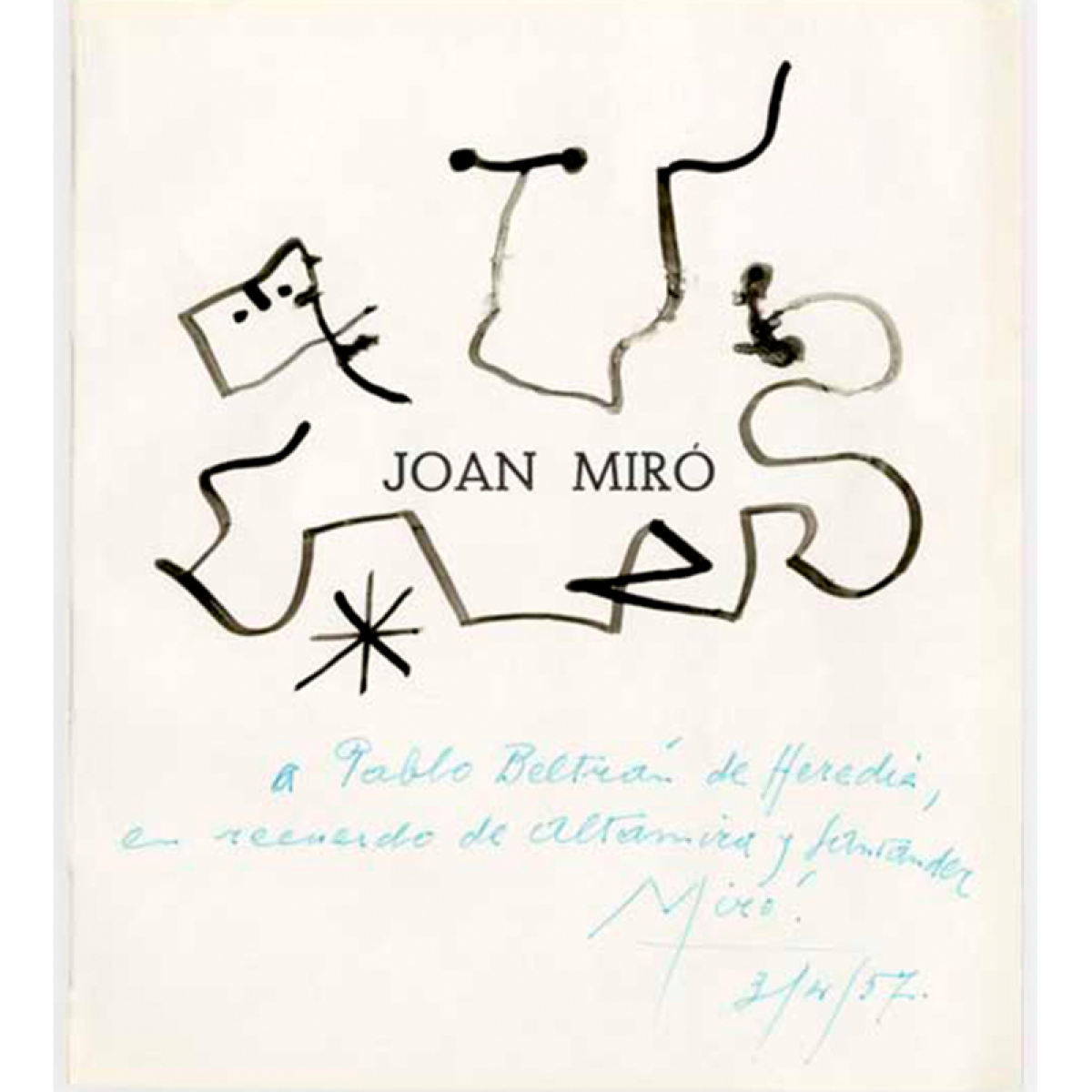

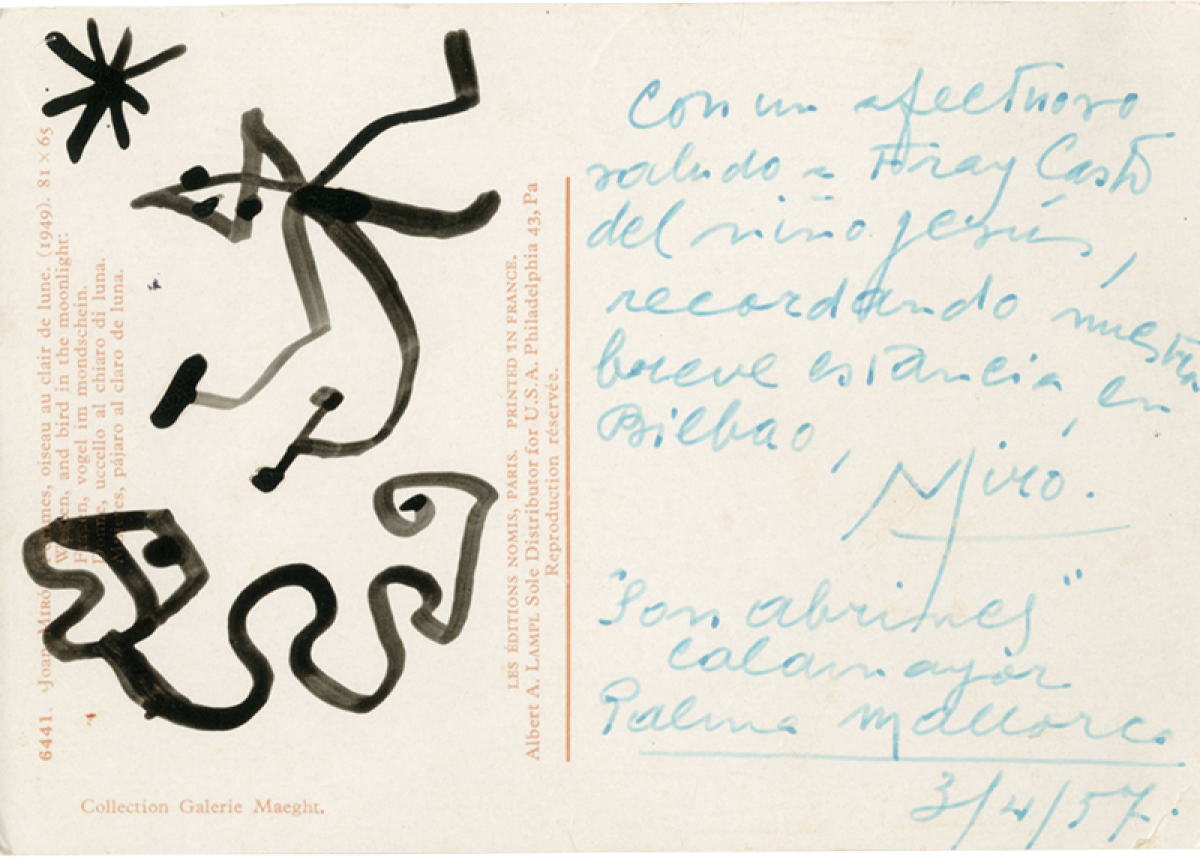

The ink-on-paper drawing «revolves» around the name of Joan Miró printed in capital letters almost in the middle of the page. Below the drawing is a text handwritten by the artist in blue ink that reads: Pablo Beltrán de Heredia, in memory of Altamira and Santander. Miró.

3/4/57

Autor: Juan Antonio González Fuentes

So begins the story I want to tell. In order for it to be properly explained we have to travel back in time a few years and in order to conclude it properly we must take it back up to 1959 and extend it for another forty years until 1999. Then the circle will be complete and closed. Let us now begin the story.

Joan Miró

Untitled, 1957. Ink on paper, 22,8 x 20 cm

The Altamira School in Santillana del Mar, 1949-1950

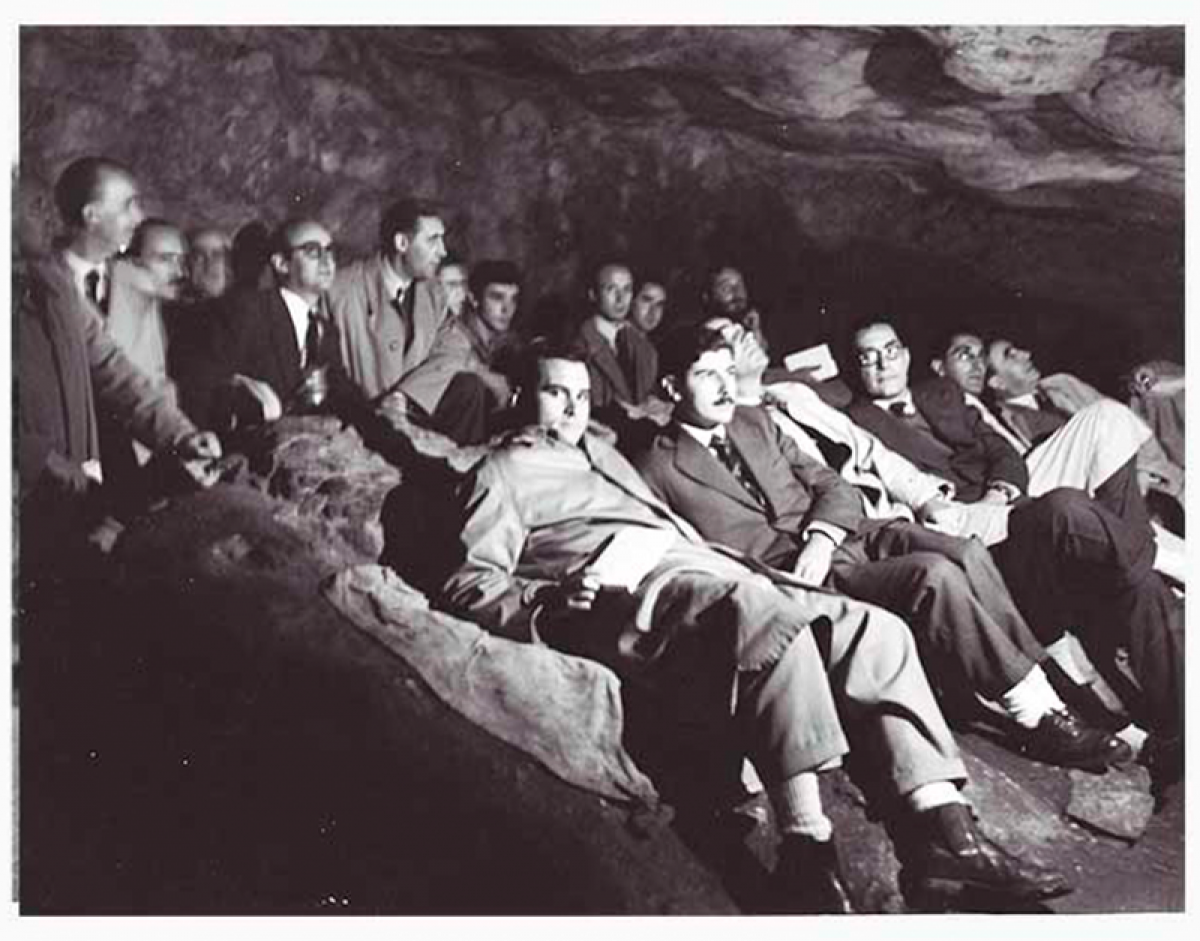

Over the course of a week in the months of September 1949 and 1950, the Altamira School’s two main Conferences were held in the Cantabrian town of Santillana del Mar. The aim of these conferences was to foster the revival of Spanish art in the postwar period, bringing it into contact with the contemporary artistic mainstream and opening it up to a less narrow and more cosmopolitan worldview.

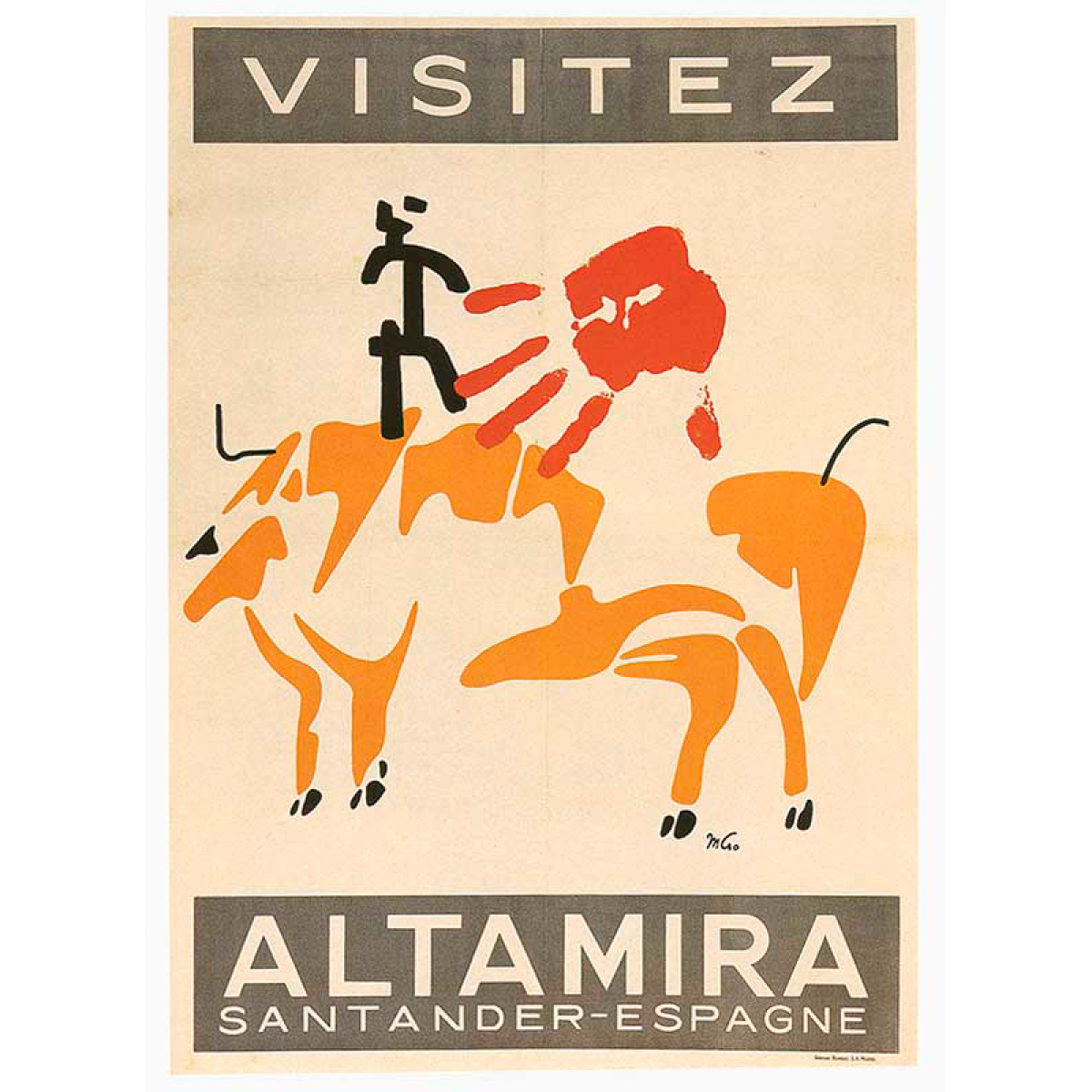

The idea originated with the German artist Mathias Goeritz in 1948, who, on discovering the rock paintings in the Altamira caves, found in them inspiration for a «New Art» rooted in prehistorical artistic expressions and also influenced by the teachings of the School of Paris, the Bauhaus, Paul Klee and Joan Miró.

Goeritz planned to bring together a colorful and international group of artists and intellectuals in Santillana del Mar (very close to the Altamira cave), where he lived at the time, to promote and encourage debate and the exchange of opinions. In addition to Goeritz himself, the driving forces behind the project were the Madrid-based sculptor Ángel Ferrant; the lawyer, writer, literary critic and future recipient of the Prince of Asturias Award for Letters, Ricardo Gullón (a public prosecutor at the time in Santander); and the historian, publisher and writer Pablo Beltrán de Heredia, to whom, almost a decade later, Miró dedicated the drawing that begins this account.

Let us pause here for a moment to ask ourselves a question that is most likely inevitable: who was Pablo Beltrán de Heredia, undoubtedly the least known of the above-mentioned personages and the thread that runs through this narrative? The answer, as it almost always is in these cases, is both straightforward and complex. He was an exceptional man, one of the figures who is key to understanding the Santander of the last century culturally and politically. The person who has written most and best about Beltrán de Heredia’s life and work is undoubtedly José María Lafuente. He wrote the books Pablo Beltrán de Heredia. La sombra recobrada (La Bahía, 2009) and Pablo Beltrán de Heredia In Memoriam (Bedia / La Bahía, 2009), and he is also the literary editor of his correspondence (1950-2004) along with the poet and painter Julio Maruri (La Bahía, 2009), all essential reading for getting to know the cultural and political life of Santander in the second half of the 20th century.

José María Lafuente: La sombra recobrada, Santander: Ediciones La Bahía, 2009

Pablo Beltrán de Heredia

When Pablo died in his adopted city in August 2009, Lafuente published an obituary in the newspaper El País in which many of the highlights of his life were recorded. These highlights are as follows: he was born in Guía de Gran Canaria in 1917, as his father, a military doctor from Salamanca, was stationed on the island. At the age of 11, he was sent to live in Salamanca with his aunt and uncle, the childless couple Enrique Sánchez Reyes and Rosario Beltrán de Heredia. In 1932, Sánchez Reyes moved to Santander when he was appointed director of the Menéndez Pelayo Library, and Pablo went to Madrid with his parents. However, from that year onwards he spent every summer in Santander at his aunt and uncle’s house. Upon completing high school in Madrid, he enrolled in the Faculty of Philosophy and Letters at that same city’s Central University (now the Complutense University), while at the same time attending courses at the El Debate school of journalism on his own.

The outbreak of the Spanish Civil War caught him by surprise in Santander, where he would reside until Franco’s army entered the city. At the end of the war he was appointed adviser to the Service for the Recovery and Defense of Artistic Heritage, a post he combined with the completion of his university studies. From 1942 onwards, while serving as the editorial secretary of the University of Madrid’s academic journal and the Revista de Indias, he worked as a teaching assistant to the chair of Modern Universal History, the Cantabrian Ciriaco Pérez Bustamante, in the Faculty of Philosophy and Letters in Madrid. In 1947, Pérez Bustamante was appointed rector of the Menéndez Pelayo International University. The courses and activities of this university are to this day based at the Palacio de la Magdalena in Santander, and Pablo joined the new rector’s team as director of the Monte Corbán University Residence, a post he held until 1953. Although at the end of the war he had already resumed his summer stays in Santander, it was from 1947 onwards that he became active socially, politically and culturally there, always shuttling between Santander and Madrid.

Among his accomplishments in the cultural arena were the following: general secretary of the Altamira School Conferences (1949-1950), partner from 1949 onwards of what was to become the historic Bedia printing house, professor in the Spanish department at the University of Texas (1966-1983), national museum advisor and member of the board of trustees of the Prado Museum in the 1970s, and director of cultural activities at the Santillana Foundation (1981-1987). In addition to all this work, he published more than a dozen books and worked as an editor and editorial director, including on titles by, among others, José Hierro, José María Gil Robles, Julio Maruri, Vicente Aleixandre, Ricardo Gullón, Claudio Rodríguez, Enrique Lafuente Ferrari, Eugenio d’Ors, Juan Benet, Ángel González, Francisco Ayala, Gerardo Diego, Luis Felipe Vivanco, Jorge Guillén, José Luis Aranguren, Blas de Otero, Jorge Campos, Julián Marías and Carlos Barral.

Having broadly introduced Beltrán de Heredia, I will take back up the thread of this story which places us in the Altamira School Conferences with Pablo acting as its general secretary and organizer of the activities complementary to the debates, as well as being in charge of the publications that were produced (Bisonte magazine, books, posters and ephemeral material).

Bisonte. Antología de la Escuela de Altamira, no. 1, Santander: Artes gráficas Hnos. Bedia, n.d. [1949?]

Mathias Goeritz: Visitez Altamira. Santander-Espagne, 1949. Poster

The Altamira Conferences

With the indispensable patronage of Joaquín Reguera Sevilla (another notable figure worthy of further study), who was the civil governor of Santander and the provincial head of the Movement, the conferences in Santillana del Mar were held in 1949 (September 19-26) and 1950 (September 21-28). Paradoxically, Mathias Goeritz was not present, as by then he was already working in Mexico where he lived for the rest of his life and produced much of his work.

Among other artists, poets and intellectuals who attended one or both of the conferences were: Willi Baumeister, Alberto Sartoris, Carla Prina, Anthony Stubbing, Ted Dyrssen, Pancho Cossío, José Hierro, Modest Cuixart, Enrique Lafuente Ferrari, Joan Teixidor, Luis Rosales, Julio Maruri, Jesús Otero, Luis Felipe Vivanco, Rafael Santos Torroella and several artists linked or related to the ADLAN group: Eudaldo Serra, Llorens Artigas, Sebastià Gasch and Eduardo Westerdahl. Also in attendance were, logically, Ángel Ferrant, Ricardo Gullón and Pablo himself.

Delegates inside the Altamira cave, second week, 1950/1981

From a historical point of view, the Altamira School achieved at least one of the objectives with which it was founded, leaving its imprint in one way or another through several institutional and private initiatives that took place at that time to connect the artistic reality of Spain with the avant-garde. We are referring to the Hispano-American Art Biennial (1951), the creation of the Museum of Contemporary Art (1952), the International Congress on Abstract Art in Santander (1953), and groups such as El Paso, Parpalló, LADAC, Taüll and the R Group. The Altamira School was also the source of enduring friendships, as we shall see below.

The promoters of the Altamira School tried to get Joan Miró, a personal friend of Llorens Artigas and a long-time leading artist of the international avant-garde (as well as a Spaniard, a circumstance that should not be disregarded in this case), to attend some of the meetings in Santillana del Mar, but the initiative did not come to fruition. The reasons for this are beyond the scope of this story, but what we must stress here is that Miró was aware of the conferences and, crucially, was interested in the possibility of one day seeing the Altamira paintings with his own eyes.

Two letters between Beltrán de Heredia and Julio Maruri from 1957: Altamira, Joan Miró, Pepito Llorens Artigas, Catalá Roca

It was almost a decade later, in early March 1957, when the occasion arose and Miró visited Santander and the Altamira cave. Logic suggests that the trip was most likely prompted by Llorens Artigas, given his friendship with Miró, who was interested in seeing the cave paintings, and with Pablo Beltrán de Heredia, who was the secretary of the Altamira Conferences in 1949 and 1950, and who in the late 1950s was still a prominent and influential figure in Santander’s political and cultural life.

Pablo Beltrán de Heredia / Julio Maruri: Correspondencia 1950-2004 (edition by José María Lafuente), Madrid: Ediciones La Bahía, 2009

Beltrán de Heredia and Julio Maruri commented on the visit in the correspondence between them which, as previously mentioned, was edited by José María Lafuente in 2009. On March 5, 1957, Pablo wrote from Santander to Julio, who after a personal crisis had left his native city, had joined the order of the Carmelites under the name Fray Casto del Niño Jesús and went to live with the Discalced Carmelites of Begoña in Bilbao:

«Dear Julio: First of all, this letter is to inform you that next Saturday, the 9th, the ineffable Pepito Artigas, his son, the painter Juan Miró and the great photographer Catalá Roca [the photos of Miró and Llorens Artigas contemplating the paintings inside the cave are his] will arrive by train from Santander, which is due to get into Bilbao at twelve o’clock. They will only be in Bilbao for a few hours, as they will be leaving on the afternoon plane that same day for Barcelona. When they come, they will only there for a couple of hours. Pepito would be thrilled to see you. Could you manage to go down to the station? He told me he’s arranging to take you to preach in Gallifa. He’s exactly the same as ever and hasn’t aged a bit. He now has a monumental project in the works, in collaboration with Miró: two large—immense—ceramic panels for the exterior façade of the UNESCO palace in Paris. In accordance with Miró’s wishes, his work will take its inspiration from the Altamira bison, the Catalan Romanesque and Gaudí’s architecture. The great assembly hall of the same building will be decorated by Picasso. It is a great triumph for Spain, or rather, for the spirit of the Spanish race…».

This paragraph reflects the close friendship that both Pablo and Julio shared with the artist José Llorens Artigas since the days of the Altamira School. For them he was Pepito Artigas, one of the three «characters» (Pepito, Llorens and Artigas) into which the artist himself divided his personality based on its different traits, as he explained to Julio Maruri in a letter which in itself is another story, another tale to be told at some point. The paragraph reproduced here is the opening paragraph of a rather long letter, and in its few lines it provides many interesting facts: the presence of Catalá Roca on the visit to Altamira, the joint Miró - Llorens Artigas project for UNESCO, the motifs Miró wanted to be present in the work…

Pablo’s letter was answered. Julio wrote to him from Begoña on March 9, 1957:

«Dear Pablo: Thanks to your letter, which arrived as punctually as it did urgently, I was able to prepare for my departure to the station. The train arrived and my disappointment was immense. Everyone had gotten off and there was no one left, when a slender young man appeared carrying photography equipment. Father Alfredo saw him before I did: "Look, isn’t that Catalá Roca? We approached him: "Excuse me, isn’t Artigas coming? Are you Catalá Roca?", "Yes, he’s coming, I’m his son". You can imagine my sigh of joy. We went into the carriage and there was Pepito, still seated, waiting for the luggage to be taken out. Miró was with him. You can imagine how thrilling that hug was for me. We walked around Bilbao together for about an hour and a half until the bus left for the airport. Joan Miró, wonderful and good to me. Pepito, charming as always. They told me you had given them each a copy of the Libro de Santillana [by Enrique Lafuente Ferrari, 1955]. "Hey, we’re going to pay the surcharge on the plane!" Artigas’s son was carrying a copy under his arm when they left for the airfield. He and Catalá Roca set off to photograph Bilbao, while we took a stroll. They even managed to get the drawbridge maneuvered to take a few shots. They came back from Altamira and Santillana delighted. As was Miró with the collegiate church…».

Julio Maruri and José Llorens Artigas during the First Congress of Altamira, 1949

These lines confirm what great friends Maruri and Artigas were from the time they met at the Altamira School in 1949, as well as underlining the fact that the visit to the cave and to Santillana del Mar pleased Miró, who did not forget either the visit or the meeting with Pablo and Julio. The evidence supporting this statement is the document that opens these pages (dated April 3, 1957) and the postcard with a drawing which the artist sent to Maruri on the same date.

Joan Miró: Untitled, 1957. Ink on postcard, 10.5 x 15 cms

A publisher called Pablo Beltrán de Heredia: his Bibliophile books

There is another, much stronger piece of evidence of the relationship that was established between Beltrán de Heredia and Miró in those days in March 1957. It has already been mentioned that from 1949 onwards Pablo was a partner-owner of the Bedia printing house. In this establishment he launched various projects over the many years of his life, but today it is perhaps his so-called Bibliophile books that best exemplify his commitment as a publisher and the quality of the works that eventually came off his press. There are three books concerned:

- Antología (1953) by José Hierro, with two drawings by Ángel Ferrant, a loose-leaf engraving by Joaquín de la Puente, a wood engraving by Ricardo Zamorano on the cover, and initials illuminated by cane pen in color by Daniel Gil. This book won José Hierro the National Poetry Prize in 1954.

- Obra poética (1957) by Julio Maruri, with lithographs made by Pancho Cossío and hand-illuminated by Alfredo Muñiz on the cover and back cover, a numbered and signed lithograph by Ricardo Zamorano, the poem «A Julio Maruri» by Vicente Aleixandre, signed by the author; colored drawings by Maruri in each of the three sections into which the book is divided, a signed text by Fray Casto del Niño Jesús dedicated to Pablo Beltrán de Heredia and, finally, a reproduction of a drawing by Ángel Ferrant dedicated to Maruri. This title won its author the National Poetry Prize in 1958.

The third of these books is of greatest interest to us in bringing our story to a close. Entitled Los encuentros (1959), by Vicente Aleixandre, a normal paperback edition of it had been released by the publisher Guadarrama just a year earlier. The Bibliophile edition prepared by Pablo includes five lithographs by Julio Maruri/Fray Casto del Niño Jesús, a portrait of Aleixandre signed by Ricardo Zamorano and by the poet himself, and the cover and back cover feature photoengravings of two gouaches by Joan Miró: El sol (cover) and La luna (back cover). The artist sent the two original gouaches to Pablo, and once the book was completed, he asked the publisher to give El sol to Vicente Aleixandre as a gift from him and to keep La luna as a personal present for himself. Pablo indeed complied with Miró’s request and delivered the splendid gift to the poet from Seville, the future winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature. Archivo Lafuente preserves four hand-signed letters from Joan Miró to Beltrán de Heredia on the subject of the gouaches used to illuminate Aleixandre’s book.

As José María Lafuente has written: «The publication of these three Bibliophile books can be considered a milestone among the publications of the time, especially taking into account the precariousness of the materials and the methods used. Gonzalo Bedia’s skill as a typographer and Pablo’s editorial oversight and taste made this small miracle possible».

Left: José Hierro: Antología, Santander: Pablo Beltrán de Heredia, 1953. Cover by Ángel Ferrant

Centre: Julio Maruri: Obra poética, Santander: Pablo Beltrán de Heredia, 1957. Cover by Pancho Cossío

Right: Vicente Aleixandre: Los encuentros: Pablo Beltrán de Heredia, 1959. Cover by Joan Miró

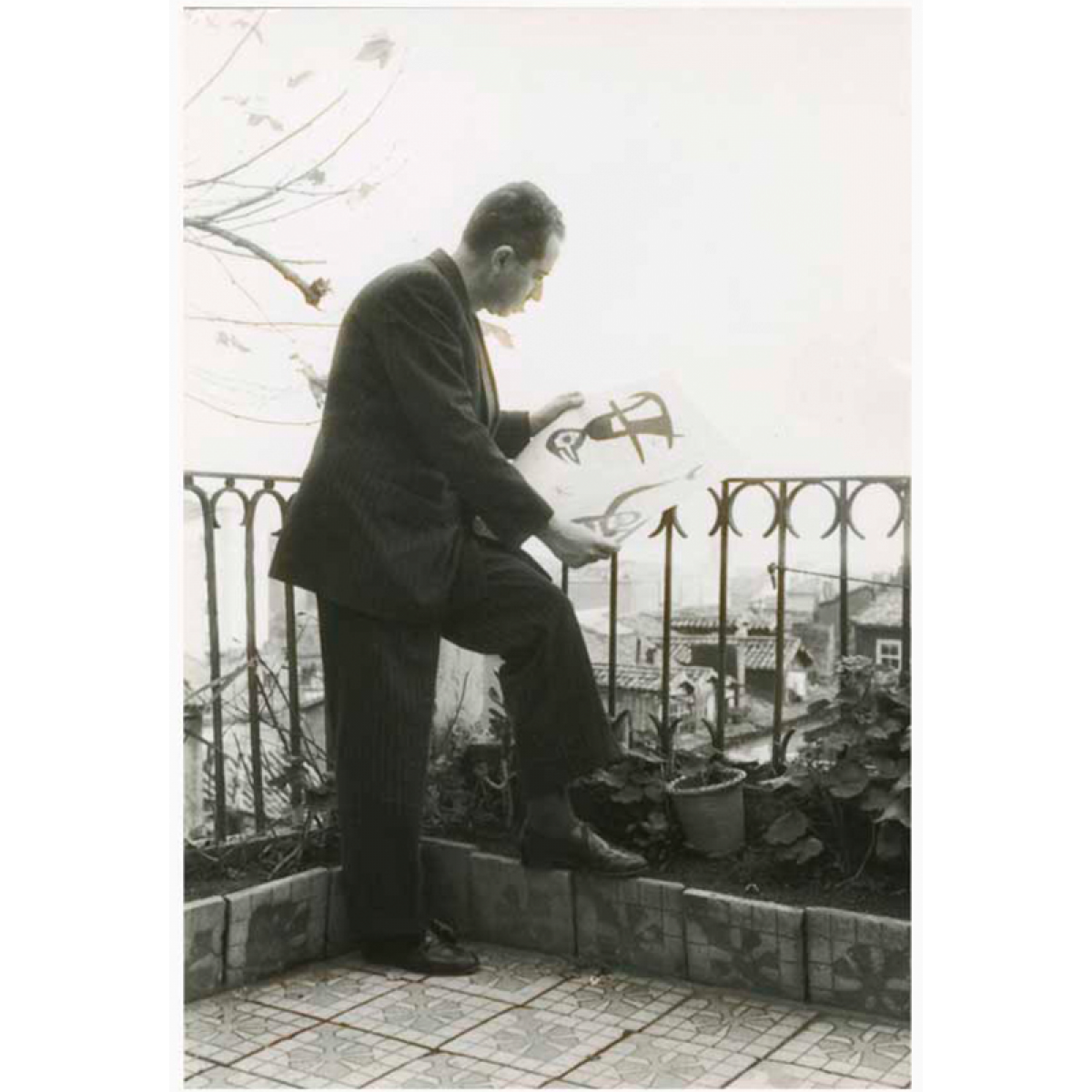

The photo that captures a «miracle»

There is a black and white photograph, apparently taken by Julio Maruri, which perfectly captures the paradoxical atmosphere in which the miracle took place. Pablo Beltrán de Heredia, positioned on a sort of balcony or terrace outside the Bedia printing house on Calle África in Santander, contemplates by the natural light of day the lithographic proofs of Joan Miró’s gouaches that will illustrate the cover and dust jacket of the book he is readying with texts by Aleixandre. In his hands he holds the proofs in which the Miró and «avant-garde» figures can be glimpsed. The person holding the work is dressed in a dark gray suit, like any other young bourgeois man in a provincial Spanish city in the late 1950s. He is standing on a balcony enclosed by a metal railing that conveys dampness and rust. The floor is tiled, reminiscent of the creation of depth of field present in the landscapes of Renaissance paintings. And between the floor and the railing is a narrow swath of dark soil carelessly inhabited by geraniums, the odd flowerpot and weeds. In the upper-left of the picture, the emaciated, almost bare branches of a feeble tree barge in.

The landscape that can be viewed from the unobstructed height of the balcony is not roundly urban in character. It is enveloped by a provincial atmosphere whose rural past has not completely vanished and is still evident. One can see tiled roofs, some old chimneys, small windows that must not close properly and, beyond that, a kind of gray mist that seems to envelop everything and detracts from the joy, liveliness, pulse and energy of the scene.

A melancholic, gray, provincial languor is the setting for the scene, yet the argument that sustains it and gives it narrative consistency is Miró’s avant-garde vision that explodes in the center of the image, calling out other worlds, other atmospheres, other experiences, other ideas, other reasons, other colors, other freer and fuller lives. Something new bursts forth in the midst of sleepy provincial statism. This is the real miracle that Maruri captures with his camera.

Here ends this story featuring the intertwined destinies of Miró, Mathias Goeritz, Llorens Artigas, Catalá Roca, Pablo Beltrán de Heredia and Julio Maruri. It is a story that tells of books, publications, poetry, cave painting, avant-garde art, conferences, talks, exchanges, and the desire and will to reconnect Spain with modernity and the avant-garde. It is a story that tells, above all, of friendship and personal relationships forged around creation and culture, and of how experiencing art and culture with passion and genuine interest can serve to break down the narrow barriers around life erected by parochialism and its fallow mindset.

Before we bring the curtain down, however, two notes. Salvador Carretero, director of the Museo de Arte Moderno y Contemporáneo de Santander y Cantabria (MAS), tells me that he remembers seeing Miró’s El Sol for sale in a gallery at Art Basel, a piece which once belonged to Aleixandre and was the cover illustration of the edition of Los encuentros released by the Bedia printing house.

Pablo Beltrán de Heredia donated the original gouache given to him by Miró to the Santander City Council so that it could be included in the collection of the then Municipal Museum of Fine Arts. He did so publicly on February 19, 1999 in the Plenary Hall of the Santander City Council building during a ceremony in which he was awarded the title of Adopted Son of Santander. Since then, La luna has been one of the best and most outstanding works in the MAS collection.

Pablo Beltrán de Heredia at the balcony of Hermanos Bedia, 1959. It seems that the author of the picture is Julio Maruri

LINKS

Escuela de Altamira in Archivo Lafuente

Mathias Goeritz in Archivo Lafuente